EXTENSIVE FACTS TAKE TIME TO LOAD

All-Illinois Society of Fine Art (1926-1963)

By Joel S. Dryer

The All-Illinois Society of the Fine Arts was founded in Chicago in 1926 under the guidance Mrs. Charles R. Dalrymple.[1] The society held annual exhibitions and other events to promote the sale of art by its members. It is likely that the group was formed in response to the Hoosier Salon Patrons Association, founded in 1924 by the Daughters of Indiana of Chicago and holding its first exhibition in 1925 at Marshall Field & Company. The All-Illinois Society of the Fine Arts continued to operate until around 1963.[2]

Their principles were clearly stated:

The object of the society is to create a better appreciation of Art in Illinois, to encourage the production and promote the sale of the work of living Illinois artists, that the artists and their work may become better known within their own State…. Our Slogan: An original work of art by an artist of Illinois in every school and home of Illinois.[3]

The… society is statewide in its scope, unifying all existing art interests in the state. It means to stimulate, promote and encourage the production of the work of Illinois artists, bringing out the real beauty, the certainty, the sentiment and poetry for which our Illinois artists are so noted. No one group or school will dominate this movement, but the highest standards in all the arts will be maintained.[4]

The plan was to establish a permanent art gallery with rotating shows, including an annual exhibition, featuring paintings, sculpture, watercolors, miniatures, etchings, and graphic arts. However, paintings, sculpture, and watercolors later dominated all exhibitions. Membership was open to anyone who paid a five-dollar fee and was not restricted to artists of a particular skill level. The group was supported by the Illinois Federation of Women’s Clubs and aimed to bring exhibitions to communities throughout Illinois.[5] Regular purchase prizes and medals were awarded at the exhibitions.[6]

The initial show was almost cancelled as many artists threatened to pull out over a controversy of whether the organization was to be “art” focused or “social” focused.[7] More controversy erupted when two juries were appointed, one “conservative” and one “modern.” Chicago Tribune critic Eleanor Jewett commented that such arrangement might border on the absurd. Each artist was to determine whether they would submit to one or the other jury. She termed the latter jury “The, possibly, radical jury.”[8] Five days later it was reported that:

Insults came thick and fast as pandemonium threatened to break up the meeting when the All-Illinois Society of Fine Arts [sic] and those artists who have entered pictures in the all-Illinois art exhibit at Carson-Piere’s galleries clashed at the City club last night. There were 256 exhibitors, all together; 73 were at the meeting.[9]

The meeting nearly erupted into violence. A large group of artists then formed their own organization, independent of the existing one, which they claimed did not adequately represent the artists’ interests, by a vote of 72 to 1. They called this new organization The Illinois Academy of Fine Arts.[10]

Despite the overwhelming support for the new organization, all agreed to continue with the first annual exhibit, which had already involved significant effort. The exhibit opened three days later, on September 27, 1926, at the galleries of Carson Pirie Scott and Company, a direct competitor of Marshall Field's.[11]

Two juries, "A" and "B," selected vastly different artwork for the exhibition.

Jury A favored traditional American Impressionist compositions known for their pleasing colors and subjects.

Jury B championed modern art with its “colorful angles and bright red parabolas and vivid yellow octagons” created by younger artists.

The two groups were hung only a few feet apart, but the distance between the two styles was “appalling,” as emphasized by artists from both sides. Despite this, a successful opening was held, attracting hundreds of exhibitors and thousands of patrons.[12]

The artwork then traveled to Springfield on November 16, where the state government appropriated $1,000 to purchase a work of art for a permanent Collection. Next it was sent successively to Decatur, Peoria, Bloomington and Jacksonville.[13]

The All-Illinois Society of the Fine Arts held its second annual exhibition in November 1927 at Chicago's Bismarck Hotel. In a significant departure from the previous year, the society restricted participation to Illinois residents exclusively. Additionally, they abandoned the traditional jury system in favor of a sole focus on purchase prizes. This bold move was likely influenced by the Chicago Galleries Association, which had also been founded in 1926. The All-Illinois Society guaranteed a substantial $15,000 for these purchase prizes, demonstrating their commitment to supporting local artists.[14]

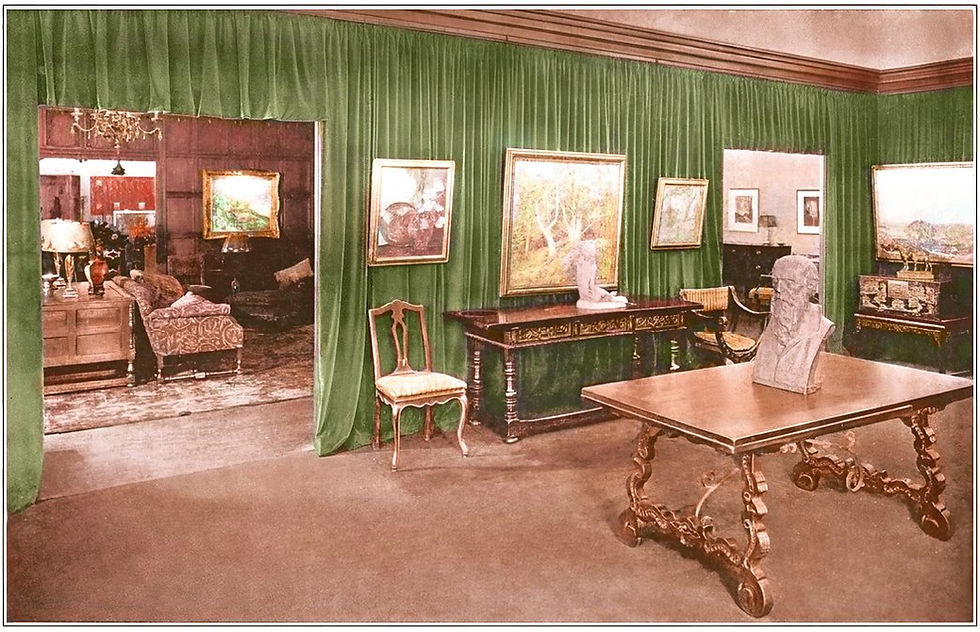

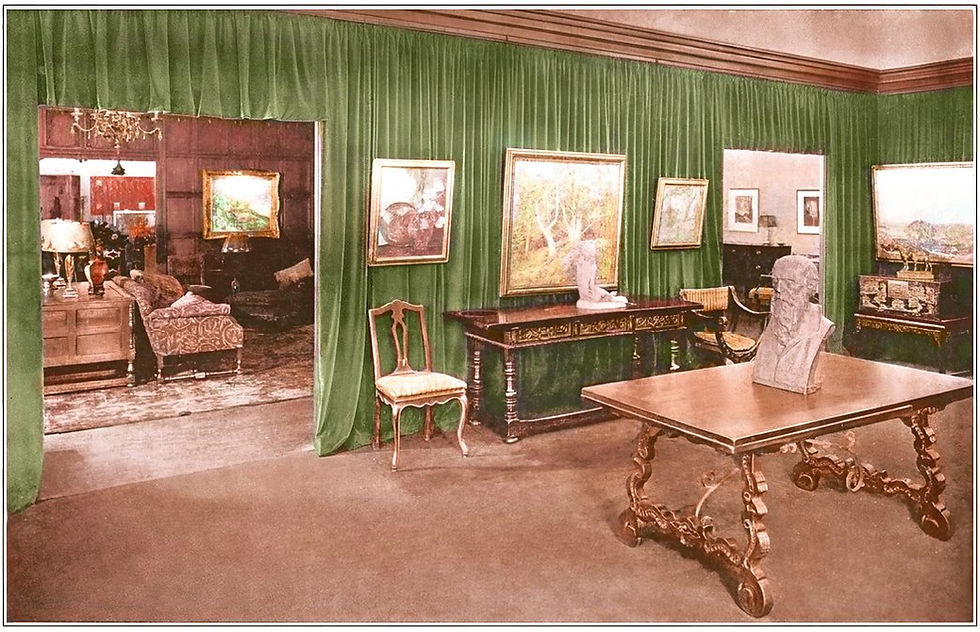

In 1930 the All-Illinois Society moved into gallery space on the fifth floor of Revell’s at Wabash and Lake in Chicago.[15] The next year, in February 1931, they removed to permanent display quarters at the Stevens Hotel, site of their annual exhibits.[16] The Stevens gave them space for a continuous display of member’s works.[17] Members were allowed to show one work and could exchange it if it hadn’t sold.[18]

The thirteenth annual show in 1939 was sternly criticized by the typically conservative critic Eleanor Jewett.

“The show is much along the same lines that previous exhibits of the society have made familiar to us… They type of picture in the current exhibit would fit easily into any Illinois home or school, but, the catch is, that with very few exceptions their entry would cause not so much as a ripple.”

“It seems to us that by imperceptible degrees the artists who make up this organization are letting it down. The jurying of the pictures is a lenient affair; the severity in jurying, it is felt, should be gin at home… But helping too many lame ducks over the stile will not in the long run benefit either the society or the artists.”

“Secondly, in the All-Illinois’ stand for sane painting, it does not bar originality of conception and execution. One might think it did to look over the rows of familiar setups offered us now at the Stevens. Originality is wanted, badly, and with it masterful execution.”

“Because there are bad drawing and a monotony of subject in other exhibits, exhibits which contain much in the way of Socialist propaganda and pseudo-French modernism, and because the All-Illinois has set its face against both these types of contemporary art is no reason why the nonmodernist painters making up its membership should lie back and be satisfied with commonplace statements of insipid ideas. We think a cold dash of water to shake them from their present apathy and self-content would be a life saver to three fourths of the list of contributing artists in the current show.”

“The banal and indifferent are as great a menace to contemporary art as are the morbid and the derivative picture. We need finer and better pictures, and we hope they will come thru the All-Illinois.”[19]

In 1941 there was no annual exhibitions as the U. S. Army had taken over the Stevens Hotel, where the group exhibited, for troops.[20] The next annual exhibition was held in January 1944, followed by a spring exhibition in April and a fall exhibition on October 29th that year. This was the continuation of the annual exhibitions, which always occurred late in the year, and marked their eighteenth annual.[21] This trend of multiple exhibits throughout the year continued at different hotels, such as the Drake and Conrad Hilton[22]. No other mention was made in the press about a single, numbered, annual exhibition, but rather annual spring, summer, fall or winter exhibitions, depending upon the time of the year they were opened. The group remained active into 1960.[23] By 1963 they had consolidated their exhibitions into space at the Palette and Chisel Club on Dearborn Street, where there was crossover in membership.[24] With no official announcement, it is presumed the organization at that point disbanded.

[1] Mrs. Charles R. Dalrymple, The All-Illinois Society of the Fine Arts - Incorporated. Century of Progress Exhibition, (Chicago: All Illinois Society of the Fine Arts, 1933), p.2. The exact date of founding was March 23.

[2] “The Sucker Salon,” Palette and Chisel, No. 20, October 1926, p.3.

[3] Op. cit., Dalrymple, The All-Illinois Society of the Fine Arts - Incorporated. Century of Progress Exhibition, p.2

[4] “All-Illinois Salon Planned for Autumn,” The Chicago Evening Post Magazine of the Art World, 6/22/1926, p.16.

[5] Lena M. McCauley, “An All-Illinois Art Crusade,” The Chicago Evening Post Magazine of the Art World, 3/16/1926, p.10.

[6] “All-Illinois Society Show Opens Sept. 27,” The Chicago Evening Post Magazine of the Art World, 8/10/1926, p.12.

[7] C. J. Bulliet, “Artless Comment,” The Chicago Evening Post Magazine of the Art World, 9/21/1926, p.8. Critic R. A. Lennon commented likewise on the almost cancelled nature of the exhibit in his review of the show, “All-Illinois Sow Reveals New Talent,” The Chicago Evening Post Magazine of the Art World, 9/28/1926, p.1.

[8] Eleanor Jewett, “Art and Artists,” Chicago Tribune, 9/19/1926, part 10, p.9.

[9] “Artists Quit Illinois Fine Arts Society in Wild, Hectic Revolt,” Chicago Tribune, 9/24/1926, p.29.

[10] Eleanor Jewett, “Art and Artists,” Chicago Tribune, 10/10/1926, part 10, p.6. Op. cit., The American Magazine of Art, Vol. 17, No. 10, October 1926, p.547. “Illinois Academy,” Art Digest, Vol. 2, 11/1/1926, p.6.

[11] All-Illinois Society of The Fine Arts, Inc. First Exhibition by Artists of Illinois, (Chicago: Carson Pirie Scott and Company, 1926), p.3.

[12] Genevieve Forbes Herrick, “Artists Forget Their Row as Exhibit Opens: Two Juries Make, O, So Different Selections,” Chicago Tribune, 9/28/1926, p.33.

[13] “An All Illinois Exhibition,” The American Magazine of Art, Vol. 17, No. 10, October 1926, p.547.

[14] Eleanor Jewett, “Art: Fall Exhibits Listed,” Chicago Tribune, 7/24/1927, part 8, p.6.

[15] “All-Illinois Society Settles in New Home at Revell’s with Three-Art, Four-Man Show,” The Chicago Evening Post Magazine Of The Art World, 1/21/1930, p.6.

[16] The sixth annual exhibit was reviewed by Tom Vickerman, “Illinois Art Calculated to Please Family,” Chicago Evening Post, 11/17/1931, Art Section, p.7, and gave credence to the conservative nature of the past shows.

[17] Tom Vickerman, “Illinois Annual Now at Stevens,” The Chicago Evening Post Magazine of the Art World, 12/2/1930, p.1.

[18] Tom Vickerman, “All-Illinois Orphan Finds Home at Last,” The Chicago Evening Post Magazine of the Art World, 2/17/1931, p.1.

[19] Eleanor Jewett, “All-Illinois Art Show Is Weak, Declares Critic,” Chicago Tribune, 12/3/1939, part 8, p.4.

[20] The inactivity is mentioned in “Chicago Artists Carry On,” Art Digest, Vol. 16, 8/1/1942, p.10. The federal government took control of The Stevens Hotel in 1941, and the Stevens brothers then sold the building to the U.S. Army. The hotel was used as a barracks and training facility for its newly enlisted servicemen – with the Grand Ballroom functioning as a mess hall. In 1945, Conrad Hilton purchased the building and today it bears his name. https://www.historichotels.org/us/hotels-resorts/hilton-chicago/history.php accessed 10/22/2024.

[21]Eleanor Jewett, “All-Illinois Fall Exhibit Opens Oct. 29,” Chicago Tribune, 9/10/1944, part 7, p.2. Jewett commented it was the 18th annual in “National Art Week Opens on Colorful Note,” Chicago Tribune, 11/5/1944, part 7, p.4.

[22] There are many instances noted in the press, for example: Eleanor Jewett, “Fine Arts Society Has Gay Exhibit,” Chicago Tribune, 6/12/1955, part 7, p.6. She discusses their “annual summer exhibition.” Eleanor Jewett, “Young Navajo’s Art Exhibition Is Impressive,” Chicago Tribune, 12/8/1948, part 3, p.14. Eleanor Jewett, “Superb Show of Fechin Art Installed Here,” Chicago Tribune, 1/7/1951, part 7, p.5.

[23] “December Art Calendar,” Chicago Tribune, 12/7/1960, part 3, p.12.

[24] “Reception to Open Fall Exhibit of Paintings,” Chicago Tribune, 9/21/1963, section 1B, p.18. After this article, no mention in the Chicago Tribune could be located.